User talk:Kaihsu/Books/EnvAB

A2 Development of international environmental law[edit source]

International environmental law.

Module A: General aspects of international environmental law I.

Chapter 2: Development of international environmental law.

Mid-19th century to 1945: beginnings[edit | edit source]

Practical and anthropocentric rather than ecological. Human-centred conservation techniques: open and closed seasons, licensing, recording/reporting, restriction on the methods of killing and tools: e.g. 1893 Pacific Fur Seal Arbitration (USA/UK), 1902 Convention for the Protection of Birds Useful to Agriculture.

‘No state has the right to use or permit the use of its territory in such a manner as to cause injury by fumes in or to the territory of another, or the properties or persons therein, when the case is of serious consequence and the injury is established by clear and convincing evidence’: 1941 Trail Smelter Arbitration (USA/Canada).

1945 to 1972: developments leading to the Stockholm Conference[edit | edit source]

- Marine pollution, e.g. the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) was created in 1957; in 1954 the London Convention on Prevention of the Pollution of the Sea by Oil – now mostly supreceded by the 1973/1978 International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL).

- Marine conservation, e.g. 1946 International Convention for Regulation of Whaling, 1959 Convention on Fishing and Conservation of the Living Resources of the High Seas (Geneva Convention).

- 1959 Antarctic Treaty

- 1971 Convention on Wetlands of International Importance (the Ramsar Convention)

- Jurisprudence: 1949 Corfu Channel (UK/Albania) confirmed Trail Smelter by finding that Albania was obliged to warn others that its territorial waters were mined. 1954 Lake Lanoux confirmed the following: state sovereignty over natural resources within their territory, cooperation, taking the interests of other states into account.

- Growing role of UN specialized agencies: e.g. FAO, IAEA, Unesco, WHO, WMO.

Founex conference 1971 and Cocoyoc Declaration 1974.

1972: Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment[edit | edit source]

This conference was around the time of the debate about a New International Economic Order. In addition to the Action Plan (109 recommendations, six areas e.g. settlements, resources, pollutants) and the recommendation on institutional and financial arrangements for the UN, there was the Declaration on the Human Environment (Stockholm Declaration). The law-related among its 26 principles:

- Principle 21 confirmed Trail Smelter: “States have, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations and the principles of international law, the sovereign right to exploit their own resources pursuant to their own environmental policies, and the responsibility to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause damage to the environment of other States or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction”.

- Principle 22: “States shall co-operate to develop further the international law regarding liability and compensation for the vIctims of pollution and other environmental damage caused by activities within the jurisdiction or control of such States to areas beyond their jurisdiction.”

- Principle 23 foresaw a limited role for international regulation.

- Principle 24 called for international organizations to play a role.

The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP; rebranded 2016 as UN Environment) was established in 1972.

1972 to 1992: developments leading to the Rio Conference[edit | edit source]

Piecemeal efforts however included important agreements, e.g.:

- 1974 Helsinki Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area

- MARPOL 1973/1978

- 1973 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES)

- 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

- 1987 Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (Montreal Protocol to 1985 Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer)

- 1978 UNEP draft Principles of Conduct in the Field of the Environment for the Guidance of States in the Conservation and Harmonious Utilisation of Natural Resources Shared by Two or More States

- 1982 World Charter for Nature, a non-binding document adopted by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN, an NGO) and the UN General Assembly.

1992: Rio Conference on Environment and Development[edit | edit source]

The 1987 report Our Common Future by the Brundtland Commission defined the term “sustainable development” as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Inspired by this, the UN Conference on the Environment and Development (UNCED) was held in Rio de Janeiro from 3 to 14 June 1992. Developing States and NGOs were involved more than in Stockholm. It adopted three non-binding instruments: the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (with 27 principles), the UNCED Forest Principles, Agenda 21; and two treaties were opened for signature: the Convention on Biological Diversity, UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The UN Commission on Sustainable Development was set up.

Principle 1, Rio Declaration: “Human beings are at the centre of concerns for sustainable development. They are entitled to a healthy and productive life in harmony with nature.”

Principle 2 (cf. Stockholm 21): “States have, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations and the principles of international law, the sovereign right to exploit their own resources pursuant to their own environmental and developmental policies, and the responsibility to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause damage to the environment of other States or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.”

Principles 3 and 4: “The right to development must be fulfilled so as to equitably meet developmental and environmental needs of present and future generations.” ¶ “In order to achieve sustainable development, environmental protection shall constitute an integral part of the development process and cannot be considered in isolation from it.”

Principle 13 (cf. Stockholm 22): “States shall develop national law regarding liability and compensation for the victims of pollution and other environmental damage. States shall also cooperate in an expeditious and more determined manner to develop further international law regarding liability and compensation for adverse effects of environmental damage caused by activities within their jurisdiction or control to areas beyond their jurisdiction.”

The declaration introduced the basic principles of environmental cooperation: e.g. Principles 7 (common but differentiated responsibilities), 15 (precautionary approach), 16 (polluter pays) and 17 (environmental impact assessment). So far, this declaration is about as close as ius cogens in international environmental law: e.g. Separate Opinion of Vice-President Weeramantry in Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros (Hungary/Slovakia).

2000 Millennium Development Goals, 2002 Johannesburg Summit[edit | edit source]

The eight Millennium Development Goals were agreed in 2000, to be achieved in 2015. Goal 7: Ensure environmental sustainability.

The World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) was held in Johannesburg from 26 August to 4 September 2002. It adopted two non-binding documents:

- the Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development

- the WSSD Plan of Implementation.

Like its successor Rio+20, the main goals were combating poverty and creating a “green” economy (“sustained growth”?).

2012 Rio+20, 2015 Sustainable Development Goals[edit | edit source]

The UN Conference on Sustainable Development (UNCSD) took place in Rio de Janeiro from 20 to 22 June 2012 and adopted The Future We Want, with 283 paragraphs but no action/implementation plan or legally-binding treaties. In 2012, the UN Environment Assembly of the UNEP was established. The Commission on Sustainable Development (from Rio 1992) was replaced by the High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development in 2013.

“We recognize that poverty eradication, changing unsustainable and promoting sustainable patterns of consumption and production, and protecting and managing the natural resource base of economic and social development are the overarching objectives of and essential requirements for sustainable development. We also reaffirm the need to achieve sustainable development by: promoting sustained, inclusive and equitable economic growth, [...]; and promoting integrated and sustainable management of natural resources and ecosystems that supports inter alia economic, social and human development[...]”: Paragraph 4, The Future We Want.

The UN General Assembly adopted ‘Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ in August 2015 with 17 Sustainable Development Goals and 169 targets.

A3 Sources of international environmental law[edit source]

International environmental law.

Module A: General aspects of international environmental law I.

Chapter 3: Sources of international environmental law.

Classical sources of international law[edit | edit source]

Article 38 ICJ Statute:

| “ | 1. The Court, whose function is to decide in accordance with international law such disputes as are submitted to it, shall apply: a. international conventions, whether general or particular, establishing rules expressly recognized by the contesting states; |

” |

Binding norms[edit | edit source]

Pacta sunt servanda; but without contract, obligation erga omnes (partes) is harder to prove: North Sea Continental Shelf cases.

Articles 42 (invocation of responsibility by an injured state) and 48 (invocation of responsibility by a State other than an injured State) of the 2001 Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts are examples of the role of the International Law Commission in codification and progressive development.

Treaties[edit | edit source]

New techniques developed for environmental treaties include non-compliance procedures and framework treaties → protocols and annexes, allowing opt-ins and simplified amendment/adjustment procedures; e.g.

- 1979 Geneva Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution

- 1985 Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer → 1987 Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer

- 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change → Kyoto Protocol, Paris Agreement.

- 2001 Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants with its annexes.

Another techniques is a universal convention → regional agreements, e.g. Article IV 1979 Bonn Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals

Conferences/Meetings of the Parties may amend or add protocols and annexes, may pass binding decisions and resolutions, may establish compliance mechanisms, etc.: e.g. Article 23 Convention on Biological Diversity.

ICJ acknowledged “evolutionary interpretation”: Namibia, Aegean Sea. When interpreting a treaty, “new [environmental] norms have to be taken into consideration, and such new standards given proper weight, not only when States contemplate new activities but also when continuing with activities begun in the past”: 1997 Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros ICJ, para 140. 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties provides for further rules of interpretation.

Customary norms[edit | edit source]

These arise when there is a practice among states to act in a particular way, or when states act because they believe that they are obliged to do so by law (opinio juris); e.g. Trail Smelter confirmed in Corfu Channel → Stockholm Principle 21 → Rio Principle 2 sic utere tuo ut alienum non laedas (use your own property in such a manner as not to injure that of another). “The existence of the general obligation of states to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction and control respect the environment of other states or of areas beyond national control is now part of the corpus of international law relating to the environment”: 1996 Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons ICJ.

Rules of customary law → codifying conventions → treaty rules for the parties; e.g. some rules of international customary law were codified in 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. But also the other way: treaty rules → rules of customary law, e.g. equitable utilisation of shared watercourses. Beyerlin and Marauhn at 19.2 lists these possible sources of customary international law:

- Exceptionally, from former ‘comity’ or ‘courtoisie’

- Uniform treaty practice

- Emerging from soft law

- Accruing from general principles of law

The provision concerned should “be of a fundamentally norm-creating character such as could be regarded as forming the basis of a general rule of law”: North Sea Continental Shelf cases page 42 at para 72. Customary norms require behaviour opinio juris sive necessitatis and consistent state practice, “even without the passage of any considerable period of time, a very widespread and representative participation in the convention might suffice of itself, provided it included that of States whose interests were specially affected” (page 42 at para 73): North Sea Continental Shelf cases; see more widely pages 41 to 43 at paras 70 to 74. Individual ‘persistent objectors’ cannot prevent the establishment of a particular customary rule; they can only avoid being bound by it. See also Nicaragua ICJ.

Ius cogens (peremptory norms)[edit | edit source]

These are norms from which no derogation is permitted; treaties are void if they conflict with ius cogens (Article 53 Vienna Convention) even if this emerges later (Article 64). E.g. prohibitions of the use of force, of slavery, of piracy, of genocide. See 1996 Nuclear Weapons Advisory Opinion ICJ.

Erga omnes (partes)[edit | edit source]

These are obligations of a State towards the international community as a whole; e.g. “outlawing of acts of aggression, and of genocide, as also from the principles and rules concerning the basic rights of the human person, including protection from slavery and racial discrimination”: Barcelona Traction (Belgium/Spain) (2nd Phase), ICJ Reports 1970, page 3 at paras 33, 34.

The obligations to preserve the environment of the high seas and in the area may be erga omnes or erga omnes partes; International Seabed Authority on behalf of humankind – as well as other entities/users/States – might be able to claim compensation: Advisory opinion of Deep Seabed Chamber ITLOS on Responsibility and Liability for International Seabed Mining (ITLOS Case No. 17).

General principles of law[edit | edit source]

Examples:

- Good faith: 1974 Nuclear Test ICJ, Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros ICJ referring to Article 26 of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.

- Equity: 1997 UN Watercourses Convention.

- Respect for mutual interests: Stockholm Principle 21 → Rio Principle 2.

Subsidiary and non-binding sources[edit | edit source]

Judicial decisions[edit | edit source]

Article 38(1)(d) ICJ Statute does not provide for stare decisis. Article 59: “The decision of the Court has no binding force except between the parties and in respect of that particular case.”

Examples of important sources:

- Arbitration cases: Trail Smelter, Pacific Fur Seal 1893; more recently 2016 South China Sea (Philippines/China) Permanent Court of Arbitration, especially VII.D protection of the marine environment, paras 815–993.

- ICJ cases: Corfu Channel, 1996 Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, 1997 Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros, 2010 Pulp Mills (Argentina/Uruguay)

- WTO Dispute Settlement Body.

Soft law[edit | edit source]

Soft law in e.g. declarations may not be legally binding, but they state principles, standards, or rules that are aspirational (potentially normative) and steer state conduct. They may later become customary international law. E.g. sustainable development, intergenerational equity, precautionary principle.

Taxonomy (Beyerlin and Marauhn, 20.2 to 20.4):

- Legally non-binding agreement between States

- political action programmes

- political declarations on existing or emerging customary norms and principles

- codes of conduct

- accords on provisional treaty implementation → catalyst for treaty-making

- Interinstitutional non-legal arrangements

- Recommendations of international organizations

Article 197 UNCLOS (Cooperation on a global or regional basis): “States shall cooperate on a global basis and, as appropriate, on a regional basis, directly or through competent international organizations, in formulating and elaborating international rules, standards and recommended practices and procedures consistent with this Convention, for the protection and preservation of the marine environment, taking into account characteristic regional features.”

Resolutions of the UN General Assembly[edit | edit source]

Even if unanimous, they are not binding, but may state customary international law and provide evidence of state practice and opinio juris, e.g. 1982 World Charter for Nature. See also Nicaragua ICJ.

A4 Jurisdictional and institutional aspects of environmental governance[edit source]

International environmental law.

Module A: General aspects of international environmental law I.

Chapter 4: Jurisdictional and institutional aspects of environmental governance.

State jurisdiction[edit | edit source]

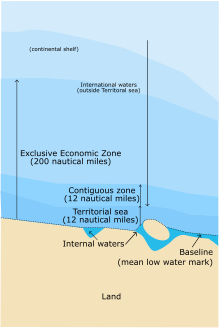

The coastal state has full jurisdiction in its internal waters (e.g. ports) and territorial sea (up to 12 nautical miles; innocent passage allowed; only criminal jurisdiction enforced). It may establish a contiguous zone up to 24 nautical miles.

Global conventions apply, e.g. MARPOL, 1972 London Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes; also regional conventions, e.g. 1992 Helsinki Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area.

Distinguish legislative from enforcement jurisdiction; flag, coastal, and port states.

Continental shelf[edit | edit source]

1958 Convention on the Continental Shelf confirmed the 1945 Truman Proclamation that the coastal state exercises exclusive sovereign rights to explore and exploit natural resources (living or mineral) in the seabed and subsoil of its continental shelf, to a depth of 200 metres.

This is further confirmed in 1969 North Sea Continental Shelf ICJ and Article 77 of 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Exclusive economic zone[edit | edit source]

Customary international law recognizes exclusive fisheries up to 200 nautical miles. EEZ extends this to ‘exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing’ both living and non-living resources: Articles 55–58 of 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. The coastal state has sovereign rights over natural resources in waters adjacent to the seabed, but freedom of navigation applies to all waters in the EEZ.

Deep seabed and high seas[edit | edit source]

The natural resources of the seabed beyond state jurisdictions are the common heritage of humankind, managed by the International Seabed Authority.

The high seas is open to all states and there is e.g. freedom of fishing, in turn limited by regional fisheries commissions and international conventions e.g. 1959 Geneva Convention on Fishing and Conservation of the Living Resources of the High Seas, 1982 UNCLOS, 1995 United Nations Agreement on the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish and Highly Migratory Stocks.

Intergovernmental organizations[edit | edit source]

An international organization such as the UN should be regarded in international law as possessing the powers which, even if they are not expressly stated in the Charter, are conferred upon the Organization as being essential to the discharge of its functions: Reparation for Injuries ICJ 1948. In contrast, WHO did not have the standing to request an advisory opinion before the ICJ: Use of Nuclear Weapons in Armed Conflict ICJ 1996.

United Nations[edit | edit source]

See Arts. 1, 55 UN Charter.

- Principal organs: General Assembly (Art. 13 Charter), Security Council, Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), Trusteeship Council, ICJ, Secretariat.

- Subsidiary organs: Committees standing and ad hoc, e.g. Commission on Sustainable Development under ECOSOC → now High-Level Political Forum (supported by UN Secretariat’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs), Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods and GHS under ECOSOC, International Law Commission.

- Specialized agencies e.g. ILO, WHO, World Bank (trustee of Global Environment Facility; with its Inspection Panel), IMF, FAO → e.g. 1993 Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas, IMO (with its Marine Environment Protection Committee) → e.g. MARPOL 73/78, WMO → IPCC. But IAEA and WTO do not formally belong to the UN System.

- Programmes and organs, e.g. UNDP, UNEP (with its UN Environment Assembly since 2014 ex General Council, Division of Environmental Law and Conventions) reporting to ECOSOC → e.g. 1998 Rotterdam PIC Convention.

Under ECOSOC, UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) has a Committee on Environmental Protection and an Environment for Europe process. It has adopted declarations and conventions e.g. Aarhus Convention ← Rio Principle 10, 1979 Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution, 1991 Espoo Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context, 1992 Helsinki Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes and 1992 Helsinki Convention on the Transboundary Effects of Industrial Accidents.

Regional organizations[edit | edit source]

European Union.

OECD has an Environment Directorate and a Environment Policy Committee (EPOC), and an Environment Strategy for the first decade of the twenty-first century guiding the work of the OECD Council. → International Energy Agency.

The Council of Europe's Pan-European Biological and Landscape Diversity Strategy led to the 2000 European Landscape Convention. It serves as the secretariat of the 1979 Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (the Bern Convention). Its European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) under the 1950 European Convention on Human Rights and Political Freedoms contributes to human rights jurisprudence about environment.

OSCE has environmental activities and Environment and Security Initiative (ENVSEC).

African Union (est. 1963 Organization of African Unity) has 1968 African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (revised 2017 Maputo), 1991 Bamako Convention on the ban on the Import into Africa and the Control of Transboundary Movement and Management of Hazardous Wastes within Africa.

ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution.

Treaty organizations[edit | edit source]

These can be commissions e.g. Helsinki Commission under 1974 Helsinki Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area, OSPAR Commission; or COPs/MOPs plus secretariats e.g. Secretariat of the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions.

UNCLOS → ITLOS and International Seabed Authority.

Non-state actors[edit | edit source]

‘The Economic and Social Council may make suitable arrangements for consultation with non-governmental organisations which are concerned with matters within its competence. Such arrangements may be made with international organisations and, where appropriate, with national organisations after consultation with the member of the United Nations’: Article 71 UN Charter. Paragraphs 11 and 12 of ECOSOC Resolution 1996/31 (Consultative relationship between the United Nations and non-governmental organizations) requires internal accountability and financial transparency of the consultative NGOs.

Examples:

- International Union for Conservation of Nature → Draft International Covenant on Environment and Development : implementing sustainability. Fifth edition : updated text.

- Article 7, paras 1–2,6 of 1992 Framework Convention on Climate Change: The COP shall ‘Seek and utilise, where appropriate, the services and cooperation of, and information provided by, competent international organisations and intergovernmental and non-governmental bodies’; ‘Any body [...] which has informed the secretariat of its wish to be represented at a session of the COP as an observer, may be so admitted unless at least one third of the parties present object.’

- Rio Summit identified a set of nine Major Groups to have a key role to play in implementing Agenda 21: Women – Children and Youth – Indigenous Peoples – Non-Governmental Organizations – Local Authorities – Workers and Trade Unions – Business and Industry – Scientific and Technological Community – Farmers.

National and international law and soft law may require or encourage the use of privately-set environmental standards or eco-labelling such as ISO 14000, Forest Stewardship Council, Marine Stewardship Council.

International environmental public–private partnerships may be listed in the Partnerships for SDGs online platform and follow UN Global Compact.

Individuals and communities[edit | edit source]

‘At the national level, each individual shall have appropriate access to information concerning the environment that is held by public authorities [...] and the opportunity to participate in decision-making processes’: Rio Principle 10 → Aarhus Convention → 2003 Kyiv Protocol on Pollutant Release and Transfer Registers. Lat. Am. and Caribbean counterpart: Escazú Agreement.

‘In view of the interrelationship between the natural environment and its sustainable development and the cultural, social, economic and physical well-being of indigenous people, national and international efforts to implement environmentally sound and sustainable development should recognize, accommodate, promote and strengthen the role of indigenous people and their communities’: Chapter 26 of Agenda 21.

‘Civil liability regimes’ recognize the need to impose obligations on private parties to protect the environment.

A5 General principles of international environmental law[edit source]

International environmental law.

Module A: General aspects of international environmental law I.

Chapter 5: General principles of international environmental law.

Taxonomy[edit | edit source]

Viñuales citing Nicaragua v Costa Rica ICJ 2015 para 104: due diligence, prevention, cooperation (notification and consultation), env. impact assessment, confirming 1996 Advisory Opinion on Nuclear Weapons and 2010 Pulp Mills.

Dupuy and Viñuales chapter 3:

- Principles and concepts: Iron Rhine (Belgium/Netherlands) 2005 Permanent Court of Arbitration

- Prevention

- Substantive principles

- "No-harm" principle (+sovereignty; Stockholm 21, Rio 2)

- Prevention principle (Stockholm 6, 7, 15, 18, 24; Rio 11, 14, 15)

- Precautionary principle (approach; Rio 15)

- Procedural principles

- Cooperation, notification, consultation (Rio 19)

- Prior informed consent

- Environmental impact assessment (Rio 17)

- Substantive principles

- Balance

- Principles

- Polluter-pays principle (Rio 16)

- Common but differentiated responsibilities

- Participation

- Inter-generational equity

- Concepts

- Sustainable development

- Common areas

- Common heritage of humankind

- Common concern of humankind

- Principles

- Prevention

“... It shall be based on the precautionary principle and on the principles that preventive action should be taken, that environmental damage should as a priority be rectified at source and that the polluter should pay”: Art. 191(2) TFEU.

Preventive principle[edit | edit source]

The obligation erga omnes to prevent, minimize/reduce, and control harm outside state jurisdiction is a rule of customary international law → due diligence, state-of-the-art/best practice. Distinguish from the stronger “no-harm” principle or prohibition of harmful activities, despite the maxim sic utere tuo ut alienum non laedas in Stockholm 21 (Nuclear Weapons ICJ), Rio 2, and UNCLOS Article 194(2).

Commentaries on draft 2001 Articles on Transboundary Harm by Intl Law Commission states “it does not guarantee that harm would not occur” (Art. 3; Part 2 para 7).

The scope of prevention may be even stronger, covering the environment in general, inside or outside the state.

Declarations[edit | edit source]

‘States shall take all possible steps to prevent pollution of the seas by substances that are liable to create hazards to human health, to harm living resources and marine life, to damage amenities or to interfere with other legitimate uses of the sea’: Stockholm Principle 7 (also see 6, 15, 18, 24). ‘States should effectively cooperate to discourage or prevent the relocation and transfer to other states of any activities and substances that cause severe environmental degradation or are found to be harmful to human health’: Rio Principle 14 (also see 11, 15). ← cf. sovereignty and "no-harm" (Trail Smelter).

Treaties[edit | edit source]

- 1982 UNCLOS Article 194(1)

- Montreal Protocol (Preamble)

- 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (Article 2).

Caselaw[edit | edit source]

"The existence of the general obligation of States to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction and control respect the environment of other States or of areas beyond national control is now part of the corpus of international law relating to the environment." (Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, Advisory Opinion, ICJ Reports 1996, pp. 241–242 para 29.

‘... mindful that, in the field of environmental protection, vigilance and prevention are required on account of the often irreversible character of damage to the environment and of the limitations inherent in the very mechanism of reparation of this type of damage’: Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros (Hungary/Slovakia) 1997 ICJ Reports 7 at p 78, para 140. Also see Iron Rhine paras 59, 222.

Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay (Argentina v. Uruguay): “the principle of prevention, as a customary rule, has its origins in the due diligence that is required of a State in its territory. It is ‘every State’s obligation not to allow knowingly its territory to be used for acts contrary to the rights of other States’ (Corfu Channel (United Kingdom v. Albania):, Merits, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1949, p. 22). A State is thus obliged to use all the means at its disposal in order to avoid activities which take place in its territory, or in any area under its jurisdiction, causing significant damage to the environment of another State.” (Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 2010 (I), pp. 55-56, para. 101.)

“[T]o fulfil its obligation to exercise due diligence in preventing significant transboundary environmental harm, a State must, before embarking on an activity having the potential adversely to affect the environment of another State, ascertain if there is a risk of significant transboundary harm, which would trigger the requirement to carry out an environmental impact assessment [...]”: 2015 case pair Certain Activities carried out by Nicaragua in the Border Area and Construction of a Road in Costa Rica along the San Juan River ICJ at para 104, citing Pulp Mills.

“At the outset, the Tribunal notes that the obligations in Part XII apply to all States with respect to the marine environment in all maritime areas, both inside the national jurisdiction of States and beyond it. Accordingly, questions of sovereignty are irrelevant to the application of Part XII of the Convention [UNCLOS]”: South China Sea PCA 2016.

Precautionary principle[edit | edit source]

This has not yet achieved the status of a customary rule of international law: more a licence to act (e.g. in trade contexts) than a command to act.

Declarations[edit | edit source]

‘In order to protect the environment, the precautionary approach shall be widely applied by states according to their capabilities. Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation’: Rio Principle 15.

Treaties[edit | edit source]

More than 50 mention this, examples: ozone, biodiversity, climate conventions. ‘The contracting parties shall apply the precautionary principle, i.e. to take preventive measures when there is reason to assume that substances or energy introduced, directly or indirectly, into the marine environment may create hazards to human health, harm to living resources and marine eco-systems, damage amenities or interfere with other legitimate uses of the sea even when there is no conclusive evidence of a causal relationship between inputs and their alleged effects’: Article 3, para.2 (Fundamental Principles and Obligations) of the 1992 Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area (Helsinki Convention).

"Each Party shall strive to adopt and implement the preventive, precautionary approach to pollution problems which entails, inter-alia, preventing the release into the environment of substances which may cause harm to humans or the environment without waiting for scientific proof regarding such harm": Article 4(3)(f) 1991 Convention on the Ban of the Import to Africa and the Control of Transboundary Movement of and Management of Hazardous Wastes within Africa (Bamako Convention).

Caselaw[edit | edit source]

Before ICJ it has been relied on (unsuccessfully) by Hungary in 1997 Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros, New Zealand in 1995 Request for an Examination of the Situation in Accordance with Paragraph 63 of the Court’s Judgment of 20 December 1974 in the Nuclear Tests; mentioned by Judge Palmer in Nuclear Tests and Judge Weeramantry in the 1996 Nuclear Weapons.

Relied on before the WTO by EU (Beef Hormones, Biotech cases). But WTO Appellate Body stated in Beef Hormones (paras 122 to 125): “the precautionary principle, at least outside the field of international environmental law, still awaits authoritative formulation”; “the precationary principle does not, by itself, and without a clear textual directive to that effect, relieve a panel from the duty of applying the normal (i.e. customary international law) principles of treaty interpretation [...]”; “precautionary principle does not override the provisions of [...] the SPS Agreement”.

Relied on before ITLOS by Ireland in 2001 MOX; by Australia & New Zealand in 1999 Southern Bluefin Tuna. ITLOS Seabed Disputes Chamber's Advisory Opinion on the Responsibilities and Obligations of States Sponsoring Persons and Entities with respect to Activities in the Area requested by the International Seabed Authority: ‘… the precautionary approach is also an integral part of the general obligation of due diligence of sponsoring States, which is applicable even outside the scope of the Regulations’ (para 131), “[t]he Chamber observes that the precautionary approach has been incorporated into a growing number of international treaties and other instruments, many of which reflect the formulation of Principle 15 of the Rio Declaration. In the view of the Chamber, this has initiated a trend towards making this approach part of customary international law” (135), ‘… “due diligence” is a variable concept. It may change over time as measures considered sufficiently diligent at a certain moment may become not diligent enough in light, for instance, of new scientific or technological knowledge’ (para 117); mining regulations on polymetallic nodules and sulphides explicitly require states and International Seabed Authority to apply Rio Declaration Principle 15; Pulp Mills ICJ referred to.

Polluter-pays principle[edit | edit source]

Beyerlin and Marauhn think this economic measure by taxation or liability could be a rule, more than just a principle, despite its unclear content and scope. It is not customary international law, but a rule within EU and OECD. Birnie et al. think this lacks normative character due to difficulty in attributing liability and allocating rights.

Declarations[edit | edit source]

‘National authorities should endeavour to promote the internalisation of environmental costs and the use of economic instruments, taking into account the approach that the polluter should, in principle, bear the costs of pollution, with due regard to the public interest and without distorting international trade and investment’: Rio Principle 16. OECD Council has advocated such internalizing measures (taxation, charges, liability) since 1972, starting with domestic and EU law.

Treaties[edit | edit source]

See e.g. 1992 Helsinki Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area, 2001 Stockholm POPs Convention. But “victim pays” the insurance or mitigation: e.g. 1960 Paris Agreement on Third Party Liability in the Field of Nuclear Energy, 1976 Rhine Chloride Pollution Convention → Rhine Chlorides case 2004.

Environmental impact assessment[edit | edit source]

The conduct of EIA is either not (yet) a norm, or it is a norm of customary international law without its content being well defined. 1987 UNEP Goals and Principles of Environmental Impact Assessment definition: ‘… an examination, analysis and assessment of planned activities with a view to ensuring environmentally sound and sustainable development.’ Cf. notification & consultation of affected states (Rio 18 emergency, 19) but no veto: Lac Lanoux arbitration tribunal.

Declarations[edit | edit source]

It started with the USA 1972 National Environmental Policy Act → Stockholm Principles 14, 15; 1975 UNEP Draft Principles (nr 5) → Rio 17: ‘Environmental impact assessment, as a national instrument, shall be undertaken for proposed activities that are likely to have a significant adverse impact on the environment and are subject to a decision of a competent national authority.’

“Any decision in respect of the authorization of an activity within the scope of the present articles shall, in particular, be based on an assessment of the possible transboundary harm caused by that activity, including any environmental impact assessment”: Art. 7 Intl Law Commission 2001 draft Articles on Transboundary Harm. World Bank has EIA procedures.

Treaties[edit | edit source]

1991 UNECE Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context (Espoo Convention): EIA should involve public participation and adequate documentation, including other states → strategic environmental assessment (SEA) in 2003 Kiev Protocol on Strategic Environmental Assessment, Article 2(6): ‘“Strategic environmental assessment” means the evaluation of the likely environmental, including health, effects, which comprises the determination of the scope of an environmental report and its preparation, the carrying out of public participation and consultations, and the taking into account of the environmental report and the results of the public participation and consultations in a plan or programme.’ Similarly 1982 UNCLOS Article 206 (→ MOX Ireland/UK ITLOS 2001, S China Sea arbitration PH/CN PCA 2016) and Antarctic Protocol.

Caselaw[edit | edit source]

Earlier, it was relied on by New Zealand in 1995 Request ... Nuclear Tests ICJ. The Court in Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros held that EIA and monitoring form a continuum of duty of diligence.

Citing the above, ‘... due diligence, and the duty of vigilance and prevention which it implies, would not be considered to have been exercised, if a party ... did not undertake an environmental impact assessment on the potential effects of such works’ (para 204ff); ‘once operations have started and, where necessary, throughout the life of the project, continuous monitoring of its effects on the environment shall be undertaken’: 2010 Pulp Mills ICJ.

Confirmed in 2015 Costa Rica/Nicaragua ICJ: “If the environmental impact assessment confirms that there is a risk of significant transboundary harm, the State planning to undertake the activity is required, in conformity with its due diligence obligation, to notify and consult in good faith with the potentially affected State, where that is necessary to determine the appropriate measures to prevent or mitigate that risk.” (Judgment, para. 104.) ‘the obligation to conduct an environmental impact assessment requires an ex ante evaluation of the risk of significant transboundary harm, and thus “an environmental impact assessment must be conducted prior to the implementation of a project”’ (para 161).

This was confirmed as equally applicable to common heritage (para 148) by ITLOS Seabed Disputes Chamber in 2011 Advisory Opinion on the Responsibilities and Obligations of States Sponsoring Persons and Entities with respect to Activities in the Area, in addition to being obligation under UNCLOS: “the obligation to conduct an environmental impact assessment is a direct obligation under the Convention and a general obligation under customary international law.” (para 145). Again confirmed in South China Sea; see also Land Reclamation, Southern Bluefin Tuna.

A6 Sustainable development[edit source]

International environmental law.

Module A: General aspects of international environmental law I.

Chapter 6: Sustainable development.

Concept[edit | edit source]

This is a policy ideal – at most a (meta-)principle if normative at all. But there are sub-norms developed from it (see below).

Declarations[edit | edit source]

1987 Brundtland Report: ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ → Rio 3 & 4 (integration), 7 (common but differentiated responsibilities), 27: ‘States and people should cooperate in good faith and in a spirit of partnership in the fulfilment of the principles embodied in this Declaration and in the further development of international law in the field of sustainable development’.

Caselaw[edit | edit source]

Confirmed in Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros para 140 (‘this need to reconcile economic development with protection of the environment is aptly expressed in the concept of sustainable development’ ... ‘look afresh’) and Pulp Mills ICJ provisional measures order at para 80. Cf. Ogoniland case 155/96 (2002) African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Shrimp–Turtle WTO.

2005 Iron Rhine (‘IJzeren Rijn’) arbitration (BE/NL): ‘Since the Stockholm Conference on the Environment in 1972 there has been a marked development of international law relating to the protection of the environment. Today, both international and EC law require the integration of appropriate environmental measures in the design and implementation of economic development activities. Principle 4 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, adopted in 1992... which reflects this trend, provides that “environmental protection shall constitute an integral part of the development process and cannot be considered in isolation from it”.’ (para 59)

Substantive aspects[edit | edit source]

Rio 3 to 8.

Sustainable utilisation[edit | edit source]

1992 conventions on climate change and biodiversity (arts. 2, 10 of the latter), 1995 UN Agreement on ... Straddling Fish Stocks ..., 1997 Convention on ... Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, 2006 International Tropical Timber Agreement.

Integration of environmental protection and economic development[edit | edit source]

Stockholm 13, Rio 4: e.g. 1994 Desertification Convention. Iron Rhine regards this as a principle of international law.

The right to development[edit | edit source]

Rio 3. 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Intergenerational equity[edit | edit source]

Stockholm 1, Rio 3 → justice, trust?

- 1972 Convention on the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (Article 4)

- 1992 Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and Lakes Article 2(5)

- 1979 Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Preamble)

- 1992 Biological Diversity Convention (Preamble)

- 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (Article 3(1)).

Pacific Fur Seal Arbitration, 1996 Advisory Opinion ... Use or Threat ... Nuclear Weapons ICJ: ‘The environment is not an abstraction but represents the living space, the quality of life and the very health of human beings, including generations unborn’ (obiter para 29). Minors–Oposa case Supreme Court of the Philippines. See also pleadings in Nauru ICJ, Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal, Judge Weeramantry’s opinions in various ICJ cases.

Intragenerational equity[edit | edit source]

Rio 5, 7: 1992 climate change convention, Article 15(7) of the 1992 Biological Diversity Convention.

Common but differentiated responsibility[edit | edit source]

Stockholm 23, Rio 7 – also 6, 8, 11. → solidarity, conditionality. Rio 7: ‘States shall cooperate in a spirit of global partnership to conserve, protect and restore the health and integrity of the earth’s ecosystem. In view of the different contributions to global environmental degradation, states have common but differentiated responsibilities. The developed countries acknowledge the responsibility that they bear in the international pursuit of sustainable development in view of the pressure their societies place on the global environment and of the technologies and financial resources they command.’ → USA interpretive statement.

Also common concern, common heritage; see e.g. various conventions → 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: ‘the special situation of developing countries, particularly the least developed and those environmentally vulnerable, shall be given special priority’ (Preamble), Articles 3(2), 4(7), 12; 1987 Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, Article 5(1). → Montreal and Kyoto protocols → exemptions, extended compliance period, financial and technical support.

ITLOS in the Area paras 153–161.

Procedural elements[edit | edit source]

Rio 10: ‘Environmental issues are best handled with the participation of all concerned citizens, at the relevant level. At the national level, each individual shall have appropriate access to information concerning the environment that is held by authorities, including information on hazardous materials and activities in their communities, and the opportunity to participate in decision-making processes. States shall facilitate and encourage public awareness and participation by making information widely available. Effective access to judicial and administrative proceedings, including redress and remedy, shall be provided.’

+ Rio 17 (environmental impact assessment)

→ 1998 Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (Aarhus, in force since 2001).

B2 State responsibility for environmental damage[edit source]

International environmental law.

Module B: General aspects of international environmental law II.

Chapter 2: State responsibility for environmental damage.

Conceptual framework[edit | edit source]

State responsibility ← (breach of peremptory norm > internationally wrongful act) > harm from non-prohibited acts → liability (cf. due diligence). How does this general intl law paradigm (based mostly on bilateral right–duty–injury) apply to the environment?

The focus has shifted from state responsibility at international law (Stockholm 22) to civil liability through domestic law (Rio 13).

Environmental damage[edit | edit source]

≈ “adverse effects”? No universal definition. 1988 Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resource Activities (CRAMRA; not in force) defines for Antarctic environment at Art. 1(15) – Antarctic Environment Protocol protects on an ecosystem basis.

≠ “pollution”, a narrower concept not covering e.g. resource overuse: Article 1(a) 1979 Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution (LRTAP Convention); Articles 1(4), 145, 194 of 1982 UNCLOS.

State responsibility[edit | edit source]

The draft 2001 Articles of the International Law Commission (ILC) on the Responsibility for Wrongful Acts set out the rules on state responsibility (following wrongful acts) – mostly about state’s failure to regulate and control transboundary harm. They are not yet adopted to become legally binding but largely reflect customary law. See particularly Articles 1, 4–11, 12.

In 1995 Request for Examination of the Situation in Accordance with Paragraph 63 of the Court’s Judgment of 20 December 1974 (New Zealand v France) ICJ (Nuclear Tests case II), New Zealand pleaded unsuccessfully that Stockholm Principle 21 reflected customary international law, Weeramantry J concurred in his dissent.

But ICJ stated in 1996 Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons: ‘The existence of the general obligation of States to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control respect the environment of other States or of areas beyond national control is now part of the corpus of international law relating to the environment’ (para 29).

Internationally wrongful act[edit | edit source]

There is an obligation to make reparations for injury caused by an internationally wrongful act: Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) 1928 Chorzów Factory, confirmed in 1990 Rainbow Warrior arbitration (violation of obligation), 1997 Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros ICJ. See ILC Articles 2, 4–11, 30, 31. The options for reparation: restitution, compensation, satisfaction (ILC Articles 35 to 37). Pulp Mills ICJ: the finding of Uruguay’s breach is itself adequate satisfaction.

Preventive measures such as impact assessment: interim orders in Land Reclamation & MOX ITLOS, Pulp Mills ICJ. But injunction to prohibit not possible: 1974 Nuclear Tests ICJ.

Standing to bring claims, incl. erga omnes: ILC articles 42, 48 (actio popularis, relevant for environment); countermeasures: Art. 49. Earlier ILC draft concept of “intl crimes” not accepted; re actio pop., erga omnes see Gatt Yellow-fin Tuna, WTO Shrimp/Turtle, ICJ Nuclear Tests (Request ... situation) despite Barcelona Traction.

Compensation[edit | edit source]

Only “financially assessable damage” is compensable: ILC Article 36. Cf. Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal.

1991 United Nations Security Council Resolution 687 states that Iraq was ‘liable under international law for any direct loss, damage, including environmental damage and the depletion of natural resources, or injury to foreign Governments, nationals and corporations’ which occurred as a result of Iraq’s unlawful invasion and occupation of Kuwait (S/RES/687 (1991)), establishing United Nations Compensation Commission, which in turn adopted its Decision 7; see particularly para 35:

| “ | These payments are available with respect to direct environmental damage and the depletion of natural resources as a result of Iraq's unlawful invasion and occupation of Kuwait. This will include losses or expenses resulting from:

(a) Abatement and prevention of environmental damage, including expenses directly relating to fighting oil fires and stemming the flow of oil in coastal and international waters; (b) Reasonable measures already taken to clean and restore the environment or future measures which can be documented as reasonably necessary to clean and restore the environment; (c) Reasonable monitoring and assessment of the environmental damage for the purposes of evaluating and abating the harm and restoring the environment; (d) Reasonable monitoring of public health and performing medical screenings for the purposes of investigation and combating increased health risks as a result of the environmental damage; and (e) Depletion of or damage to natural resources. |

” |

In Certain Activities carried out by Nicaragua in the Border Area (Costa Rica v Nicaragua) 2018 compensation judgment, ICJ dismissed both Costa Rica’s “ecosystem services approach” and Nicaragua’s “replacement cost approach” but introduced its own “overall valuation”, taking into account that Nicaragua’s unlawful activities resulted in Costa Rica incurring costs (e.g. repairing damage) and capacity of natural repair, citing equitable considerations, Trail Smelter.

International crimes[edit | edit source]

Article 19 of 1980 Draft Articles on State Responsibility (environmental damage may amount to an ‘international crime’) was deleted and replaced by 2001 ILC Articles 40 and 41 (‘serious breaches of obligations under peremptory norms of general international law’), making it less relevant for international environmental law.

Sometimes international treaties are enforced through domestic (administrative or criminal) law. E.g. protective principle in the law of the sea extends coastal criminal jurisdiction in EEZ to protect marine environment. Cf. Article 218 UNCLOS.

Widespread environmental damage[edit | edit source]

ILC 1996 Draft Code of Crimes against the Peace and Security of Mankind identify widespread environmental damage when at war as a crime: art. 20(g) → 1998 Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) defines such in Article 8(2)(b)(iv). See 1998 Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of the Environment through Criminal Law (not in force).

State liability[edit | edit source]

Liability may follow from harm due to lawful but (ultra-)hazardous acts. Distinguish from civil liability (polluter pays). For state liability, there are 2001 Articles on the Prevention of Transboundary Harm from Hazardous Activities and 2006 Draft Principles on the Allocation of Loss in the Case of Transboundary Harm Arising out of Hazardous Activities.

Threshold at which damage entails liability[edit | edit source]

Roughly speaking, states must act with due diligence to prevent significant harm: Stockholm 21/Rio 2. No universal standard threshold, but words such as ‘significant’ (ILC draft Allocation of Loss Principles), ‘appreciable’ or ‘substantial’ are often used in conventions; also ‘serious’, ‘above tolerable levels’.

Standard of care[edit | edit source]

Options for standard of care: due diligence (general rule unless treaty law provides otherwise), fault liability, strict liability (no-fault but defences possible), absolute liability (e.g. nuclear, oil transport by sea). No general need to prove “fault” stricto sensu as the state’s mens rea or malice. See Article II 1972 Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects.

Treaties establishing state liability[edit | edit source]

Cf. 2010 Nagoya-Kuala Lumpur Supplementary Liability Protocol (biodiversity).

Outer space[edit | edit source]

The relevant provisions are 1972 Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects (Space Liability Convention) Article I, II, VI, VII. The only claim so far is Kosmos 954 (Canada v USSR), settled by an ex gratia payment from USSR.

Sea ‘Area’[edit | edit source]

1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of Sea (UNCLOS): State parties and international organisations have the responsibility to ensure that activities in the Area carried out by them, their nationals or by those effectively controlled by them or their nationals, comply with the UNCLOS rules on the Area (seabed and ocean floor and subsoil beyond the limits of national jurisdiction): Article 139; states are themselves ‘responsible for the fulfilment of their international obligations concerning the protection and preservation of the marine environment. They shall be liable in accordance with international law’: Article 235(1).

State liability if fail to meet its obligations to secure compliance, but otherwise liability is with the operator; no residual liability for the sponsoring state: ITLOS Advisory Opinion ... in the Area.

Hazardous activities of states[edit | edit source]

See e.g. Articles 1, 8 of 1988 Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resource Activities (CRAMRA; not in force) → Antarctic Environment Protocol art. 7 prohibits mineral resource activities; state liability rules similar to UNCLOS.

1992 Climate Change Convention Article 4(4) requires developed country parties listed in Annex II and the EU to 'assist the developing countries parties that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change in meeting costs of adaptation to those adverse effects', but like the 2015 Paris Agreement, there is no liability.

State obligation to provide funds[edit | edit source]

In case where a civil party is unable to meet all the costs of environmental damage: 1960 OECD Convention on Third Party Liability in the Field of Nuclear Energy (Paris Convention); 1963 OECD Agreement Supplementary to the Paris Convention of 1960 on Third Party Liability in the Field of Nuclear Energy (Vienna Convention); ILC allocation of loss principles. Contrast with UNCLOS, Antarctic env. protocol.

B3 Civil liability regimes[edit source]

International environmental law.

Module B: General aspects of international environmental law II.

Chapter 3: Civil liability regimes.

Nature of civil liability regimes[edit | edit source]

States parties of these conventions undertake to establish regimes in national laws to impose liability on civil parties responsible for causing damage (primarily from ultrahazardous activities). The conventions:

- define the nature of damage and liability for it (incl. maximum, minimum) – absolute, strict, fault; joint, several; exemptions – channelling: who is/are liable (shipowner, nuclear operator)

- provide for access to judicial process to enforce liability and obtain compensation (also for non-nationals – nondiscrimination): choice of forum, recognition of judgment

- provide financial mechanisms (funds, insurance) to ensure that liable civil parties are able to meet their liabilities; or even residual state liability and supplementary compensation from public funds (tiered system).

Polluter pays?

Nuclear installations[edit | edit source]

Near-absolute liability on the operator (whether state or private party), with few exceptions. Compulsory insurance or security. Ratification coverage of nuclear states is poor (USA, Canada, Japan not party to any) and no claims under the international regimes so far.

OECD Nuclear Energy Agency 1960 Paris Convention (amended 1964, 1982; max. 15 MSDR, env. damage not covered)

- → 2004 Protocol (not in force; no limit for operator liability; env. covered for economic loss, reinstatement, preventive measures; max. .7+.5+.3=1.5 GSDR)

- – 1963 Brussels Convention (supplementary compensation from public funds; so max. 15+160+125=300 MSDR).

IAEA 1963 Vienna Convention (max. 300 MSDR)

- → 1997 Protocol to amend (in force since 4 October 2003)

- – 1997 Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage standalone but related to the Vienna and Paris regimes (in force since 15 April 2015; max. +≈ 300 MSDR).

These two regimes were combined by 1988 Joint Protocol[1] with a choice-of-law rule.

The operator liability is in the low millions, the compensation from funds in the mid to high millions, but actual cost so far has been in the low billions for each incident, and actual damage estimated to be in the high billions (ultimately a political decision). Enough? Polluter pays? Patchwork anyway.

Oil pollution and wrecks[edit | edit source]

IMO two-tier regime:

- 1992 [1969] Civil Liability Convention (last amended 2000; max. ≈ 360 MSDR) provides for shipowner's strict liability for pollution damage, compulsory insurance, limit 14 MSDR.

- 1992 [1971] Fund Convention (with optional third-tier Supplementary Fund Protocol, in force 2005; max. 750 MSDR) established the International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund (last amended 2000, max. 203 MSDR).

These are widely used for claims, total ceiling ≈ 1.16 GUSD. Only actual env. restoration and damage prevention costs are compensated, but see Italian courts in Patmos, Haven and French courts in Erica. There are also private compensation schemes.

IMO 2001 Bunker Oil Pollution Convention has been in force since 2008.

IMO 2007 Nairobi International Convention on the Removal of Wrecks entered into force on 14 April 2015. There are a couple more liability conventions (e.g. Black Sea) on marine pollution, not in force.

Waste[edit | edit source]

1999 Protocol on Liability and Compensation for Damage Resulting from Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal to the 1989 Basel Convention (not yet in force) provides for strict liability on the part of the exporter or the disposer (Article 4); and fault liability in case of failure to comply with the convention or damage occurs because of intentional, reckless or negligent acts or omissions (Article 5). (Basel ban amendment of hazard waste transfer between developed and developing states has not come into force.)

Transport[edit | edit source]

- UNECE 1989 Geneva Convention on Civil Liability for Damage Caused during Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road, Rail and Inland Navigation Vessels (1989 CRTD, not yet in force)

- IMO 1996 International Convention on Liability and Compensation for Damage in Connection with the Carriage of Hazardous and Noxious Substances by Sea (1966 HNS Convention, not yet in force), based on the 1992 CLC and the 1992 Fund Convention.

Attempts at general regimes[edit | edit source]

Cf. ILC principles on loss allocation etc. See Annex VI Antarctic Env. Protocol (not in force), 2010 Nagoya–KL Liability Protocol to Biosafety Protocol (biodiversity, in force since 2018).

- 1993 Council of Europe Convention on Civil Liability for Damage Resulting from Activities Dangerous to the Environment (Lugano Convention; not yet in force)

- 2003 UNECE Protocol on Civil Liability and Compensation for Damage Caused by the Transboundary Effects of Industrial Accidents on Transboundary Waters (Transboundary Damage Protocol; not yet in force) ← 1992 UN Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes, 1992 Convention on the Transboundary Effects of Industrial Accidents

- EU Directive 2004/35/EC of 21 April 2004 on environmental liability with regard to the prevention and remedying of environmental damage.

B4 Environmental dispute resolution[edit source]

International environmental law.

Module B: General aspects of international environmental law II.

Chapter 4: Environmental dispute resolution.

Diplomatic means of dispute settlement[edit | edit source]

See UN Charter Articles 2 and 33.

1985 Vienna Ozone Convention, Article 11: “1. In the event of a dispute between Parties concerning the interpretation or application of this Convention, the parties concerned shall seek solution by negotiation. – 2. If the parties concerned cannot reach agreement by negotiation, they may jointly seek the good offices of, or request mediation by, a third party.”

Negotiation[edit | edit source]

1974 Fisheries Jurisdiction ICJ para 73: ‘The most appropriate method for the solution of the dispute is clearly that of negotiation. Its objective should be the delimitation of the rights and interests of the Parties, the preferential rights of the coastal State on the one hand and the rights of the Applicant on the other, to balance and regulate equitably questions such as those of catch-limitation, share allocations and "related restrictions concerning" areas closed to fishing, number and type of vessels allowed and forms of control of the agreed provisions" [...]. This necessitates detailed scientific knowledge of the fishing grounds. It is obvious that the relevant information and expertise would be mainly in the possession of the Parties. The Court would, for this reason, meet with difficulties if it were itself to attempt to lay down a precise scheme for an equitable adjustment of the rights involved. It is thus obvious that both in regard to merits and to jurisdiction the Court only pronounces on the case which is before it and not on any hypothetical situation which might arise in the future.’

Consultation[edit | edit source]

Some environmental treaties require consultation in e.g. authorization of harmful activities and development plans. 1979 LRTAP Convention Article 5 requires early consultations to be held between:

- parties ‘actually affected by or exposed to a significant risk of long-range transboundary air pollution’ and

- parties in which a significant contribution to such pollution originates.

1957 Lake Lanoux arbitral tribunal held that France had a duty to consult with Spain over certain projects likely to affect Spanish interests.

Also Gabcikovo-Nagymaros, Pulp Mills.

Mediation (good offices) and conciliation, fact-finding inquiry[edit | edit source]

See Article 9 of ILC 2001 Articles on the Prevention of Transboundary Harm from Hazardous Activities.

Article 33 of the 1997 UN Watercourse Convention: “[...] 2. If the parties concerned cannot reach agreement by negotiation requested by one of them, they may jointly seek the good offices of, or request mediation or conciliation by, a third party, or make use, as appropriate, of any joint watercourse institutions that may have been established by them or agree to submit the dispute to arbitration or to the International Court of Justice. – 3. Subject to the operation of paragraph 10, if after six months from the time of the request for negotiations referred to in paragraph 2, the parties concerned have not been able to settle their dispute through negotiation or any other means referred to in paragraph 2, the dispute shall be submitted, at the request of any of the parties to the dispute, to impartial fact-finding in accordance with paragraphs 4 to 9, unless the parties otherwise agree. – 4. A fact-finding Commission shall be established, [...].”

Legal means of settling disputes – “adjudication”[edit | edit source]

Any judicial process trumps other dispute settlement procedures.

Arbitration[edit | edit source]

- 1973 CITES, Article 18

- 1992 Climate Change Convention, Article 14

- 1979 Berne Convention on Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats, Article 18(2): “Any dispute between Contracting Parties concerning the interpretation or application of this Convention which has not been settled on the basis of the provisions of the preceding paragraph or by negotiation between the parties concerned shall, unless the said parties agree otherwise, be submitted, at the request of one of them, to arbitration. Each party shall designate an arbitrator and the two arbitrators shall designate a third arbitrator. Subject to the provisions of paragraph 3 of this article, if one of the parties has not designated its arbitrator within the three months following the request for arbitration, he shall be designated at the request of the other party by the President of the European Court of Human Rights within a further three months' period. The same procedure shall be observed if the arbitrators cannot agree on the choice of the third arbitrator within the three months following the designation of the two first arbitrators.”

Arbitration caselaw: 1893 Pacific Fur Seals – 1935/41 Trail Smelter – 1957 Lake Lanoux.

ITLOS order followed by UNCLOS Annex VII tribunals/PCA awards: 1999 Southern Bluefin Tuna – 2001 MOX Plant. S China Sea.

Land Reclamation UNCLOS Annex VII tribunal.

PCA awards: N Atlantic Fisheries, Iron Rhine, Rhine chlorides.

International Court of Justice[edit | edit source]

No priority or general jurisdiction; only states have standing: Chapter II, Statute esp. art. 36(2) (opt-in compulsory jurisdiction). In July 1993 the ICJ established a seven-member permanent Chamber for Environmental Matters under Article 26(1) of its Statute, “which was periodically reconstituted until 2006. However, in the Chamber’s 13 years of existence no State ever requested that a case be dealt with by it. The Court consequently decided in 2006 not to hold elections for a Bench for the said Chamber.”

ICJ environment caselaw: e.g. 1997 Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros. Test for interim measures: Pulp Mills, Costa Rica v Nicaragua.

1996 Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons paras 27 to 30: Stockholm 21/Rio 2 (no damage outside state’s own jurisdiction) cited; “The Court recognizes that the environment is under daily threat and that the use of nuclear weapons could constitute a catastrophe for the environment. The Court also recognizes that the environment is not an abstraction but represents the living space, the quality of life and the very health of human beings, including generations unborn. The existence of the general obligation of States to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction and control respect the environment of other States or of areas beyond national control is now part of the corpus of international law relating to the environment” (para 29); citing Rio 24 “Warfare is inherently destructive of sustainable development. States shall therefore respect international law providing protection for the environment in times of armed conflict and cooperate in its further development, as necessary.”

International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea[edit | edit source]

UNCLOS (Part XV) esp. Art. 287 allows choice of forum: arbitration, ICJ, ITLOS.

The International Seabed Authority is the only international organization with standing to sue states.

ITLOS arbitration cases on precautionary principle: 1999 Southern Bluefin Tuna under UNCLOS Annex VII – 2001 MOX. ITLOS can prescribe provisional measures before arbitration panel is constituted.

World Trade Organization (quasi-judicial)[edit | edit source]

Restriction measures under e.g. Montreal Protocol may clash with WTO/Gatt free trade rules.

1994 WTO Agreement (see esp. Articles III and IV) introduced the Annex ‘Understandingon Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes (DSU)’, establishing

- Dispute Settlement Body (DSB)

- ad hoc panels (EU–Biotech on genetically modified organisms)

- Appellate Body, based in Geneva (see Beef Hormones on precautionary principle, Shrimp/Turtle, Asbestos).

Panel recommendation (and Appellate Body report) is adopted by DSB unless consensus against.

Non-compliance procedures[edit | edit source]

These focus on prevention and (state) participation to facilitate; plus threat of punitive enforcement measures for deterrence – carrots and sticks. Compliance control (quasi-judicial? due process): Trigger (states reporting) – verification (NGO?) – evaluation (political?) – measure to redress. Compliance assistance (World Heritage, Ramsay wetlands inter alia): capacity-building, technology transfer, financial mechanisms (e.g. Global Environment Facility). Multilateral to address obligations erga omnes partes against free riders in the commons. Minamata Convention art. 15 provides for a compliance mechanism directly. Also inspection procedures of e.g. World Bank.

CITES[edit | edit source]

Procedures since 2007. Committee is controlled by COP; possible trade measures.

Montreal Protocol[edit | edit source]

Implementation Committee communicates with the parties on monitoring non-compliance and (with Secretariat) may report to the Meeting of the Parties. Financing and substance trade eligibility can be withdrawn if not compliant.

Conditionality: party can claim insufficient resources to preclude non-compliance procedure: art. 5. Multilateral Fund.

UNFCCC[edit | edit source]

Kyoto Protocol[edit | edit source]

7th COP (Marrakesh 2001) and 1st MOP (Montreal 2005) adopted the non-compliance mechanism for Annex I parties under Article 18 of the Protocol, with Facilitative (little used, 1 case so far) and Enforcement Branches in Compliance Committee (1st meeting Bonn March 2006). In addition, there are review/transparency processes – Measurement, reporting and verification (MRV); Multilateral Consultative Process → after Cancún since 2014: International Assessment and Review (IAR) for developed countries and International Consultation and Analysis (ICA) for developing ones.

The Enforcement Branch dealt with a dozen cases so far, first Greece; Croatia first appeal, eventually withdrawn. Canada led to withdrawal from Protocol. See informal information notes by the secretariat on questions of implementation considered by the enforcement branch. “Consequences” include ineligibility to participate in joint implementation (Article 6), Clean Development Mechanism (Article 12), and emissions trading (Article 17).

Paris Agreement[edit | edit source]

‘1. A mechanism to facilitate implementation of and promote compliance with the provisions of this Agreement is hereby established. 2. The mechanism referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article shall consist of a committee that shall be expert-based and facilitative in nature and function in a manner that is transparent, non-adversarial and non-punitive. The committee shall pay particular attention to the respective national capabilities and circumstances of Parties’: Article 15. COP24 Katowice 2018 has not agreed on a compliance committee.

1998 UNECE Aarhus Convention[edit | edit source]

Mechanism since 2002. Committee-proposed means must be approved by MOP. Civil society participation is welcome, and the vast majority of the Committee's workload has been triggered by communications from the public.

In 2011 the Committee found recourse to CJEU not satisfactory under the Convention.

Cf. NAFTA Commission on Env. Coop.

1992 Biodiversity Convention, Cartagena Biosafety Protocol[edit | edit source]

Technology transfer: art. 16.

Compliance procedures and mechanisms are set out in MOP 1 Decision BS-I/7. Compliance Committee has no mandate to consider NGO submissions. It will only consider facilitative and supportive measures when a party self-refers.

Rotterdam Convention[edit | edit source]

Compliance mechanism agreed in COP spring 2019.

B5 Human rights and the environment[edit source]

International environmental law.

Module B: General aspects of international environmental law II.

Chapter 5: Human rights and the environment.

UN, regional, national instruments[edit | edit source]

States must respect, protect, (promote,) and fulfil the rights. But there may be conflicts, balances, tradeoffs between rights – not point out in UN High Commissioner for Human Rights analytical study (2011).

United Nations[edit | edit source]

Recall Stockholm 1/Rio 1. Usually any provision for environmental right is vague, and link from other human rights to the environment is not explicit.

- 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- 1966 Covenants on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) (art. 12(2)(b) env. and industrial hygiene).

UN Human Rights Council and High Commissioner have a Special Rapporteur on the implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes (special rapporteur on toxics). Since 2012 there is a Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment.

General Comment 15 of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (under ECOSOC) affirmed the existence of the right to water → Protocol on Water and Health to the 1992 Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes (Helsinki Convention).

In August 2019, the UN Human Rights Committee found Paraguay responsible for human rights violations in context of massive agrochemical fumigations.

Regional[edit | edit source]

These regional human rights treaties:

- 1950 European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR)

- 1961 European Social Charter (ESC; revised 1996): art. 11 (health)

- 1969 American Convention on Human Rights (1969 ACHR, “Pact of San José”)

- 1981 African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (1981 African Charter).

- 2004 Arab Charter on Human Rights

Only Art. 24 African Charter, Art. 11 San Salvador Protocol to the American Convention, and art. 38 Arab Charter contain an explicit right to a satisfactory/healthy environment. San Salvador Protocol distinguishes the right of an individual to ‘live in a healthy environment’ from the positive obligation of states to protect, preserve, and improve the environment.

UNECE Aarhus Convention (1998) implements Rio 10 by providing for extensive procedural human rights: information – public participation – environmental justice → 2003 Kyiv Protocol on Pollutant Release and Transfer Registers (in force since 8 October 2009). Implemented in EU law. See User:Kaihsu/EnvA4. This further develops from Art. 9 1992 OSPAR Convention, which provides for access to info → MOX arbitration.

2012 ASEAN Human Rights Declaration provides in Article 28 the right of “every person ... to an adequate standard of living ... including ... (e) The right to a safe, clean and sustainable environment”.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, there is the 2018 Escazú Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters.

National[edit | edit source]

Like over 100 constitutions, section 24 of 1997 South Africa Constitution provides for environmental rights. Finnish constitution: ‘20 § (Vastuu ympäristöstä) Vastuu luonnosta ja sen monimuotoisuudesta, ympäristöstä ja kulttuuriperinnöstä kuuluu kaikille. ¶ Julkisen vallan on pyrittävä turvaamaan jokaiselle oikeus terveelliseen ympäristöön sekä mahdollisuus vaikuttaa elinympäristöään koskevaan päätöksentekoon.’