Today: my third (and, I think, final) thought on the “humans are unique among the animals” thread. [First installment here. Second installment here.]

In the first installment, I quoted Guy Consolmagno as saying that humans are unique in having “this curiosity to understand.” That made me think about what other aspects of our thoughts, personalities, and behaviours are unique, at least as we perceive it. Are we the only species that would be thinking about this, for example? Are we unique in thinking philosophically?

There are certainly many who think we’re the only animals with a sense of morality. One view is that morality comes from God, and that God gave it to us alone — some consequence of an apple and a snake, and whatnot, and then a fall from grace, and Cain being the first murderer, and such.

Do other animals have morality? If it’s unique to us, what, exactly, does that mean?

We appear to be the only animals who commit arbitrary acts of murder and violence against each other. A bear doesn’t wait behind a tree to attack the next bear that comes by. A zebra doesn’t find a family of zebras at night, and trample them in their sleep. Mobs of sharks don’t gather and attack other sharks whose skin is a different shade. And two male snakes who share a nest needn’t fear from other snakes who think they’re an abomination.

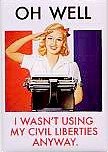

We use our “uniqueness” to exert control over other animals, including each other, and it seems we’re the only animals that do that — that tell others of our kind what they may and may not do, that imprison or kill others of our kind who don’t behave “properly”. In the animal kingdom, if you don’t follow a pack leader’s rules, you’ll be driven from the pack... but you’ll be free to go off and make a life on your own, in your own way.

We’re the only ones who will track you down and make you comply or pay the price. We’re the only ones who impose the behavioural norms of some on others — who fight wars to do so. And each of us has a different tolerance for different behaviours; each of us draws his lines in different places. That makes it particularly challenging when groups with different sensibilities mix.

If we’re the only animals who mistreat each other based on different appearance, different social behaviour, different thoughts and beliefs... that makes us unique, but it doesn’t make us better.

I’ve always loved

I’ve always loved