Hillary Clinton’s had a minor kerfuffle this week. It seems that, to support her claim to more experience than Barack Obama, she told a bit of a tale:

Hillary Clinton’s had a minor kerfuffle this week. It seems that, to support her claim to more experience than Barack Obama, she told a bit of a tale:

BLUE BELL, Pa. — As part of her argument that she has the best experience and instincts to deal with a sudden crisis as president, Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton recently offered a vivid description of having to run across a tarmac to avoid sniper fire after landing in Bosnia as first lady in 1996.

Now, I, for one, would not think someone more nor less qualified to lead the country, simply on the basis of her having been shot at. That may be a dramatic story, but it’s... well, it’s just irrelevant, isn’t it?

It’s also not true. And it didn’t take long for footage and photos, like the one at the right from the New York Times (click to enlarge), of a calm arrival to show up and refute her story. The camera, it is said, does not lie (though we can do amazing things with Photoshop these days, but never mind), and Senator Clinton had to admit that she did. Lie.

Mrs. Clinton corrected herself at a meeting with the Philadelphia Daily News editorial board; she did not explain why she had misspoken, but only admitted it and then offered a less dramatic description.Mrs. Clinton said she had been told “that we had to land a certain way and move quickly because of the threat of sniper fire,” not that actual shots were being fired.

“So I misspoke,” she said.

Of course, she doesn’t really have to “explain why she had misspoken”; the reason is clear. It leaves us wondering, though, how she imagined she wouldn’t be caught at it, and that leads us down the long, winding Misspeakippi River.

Not terribly long ago, Alberto Gonzales, then Attorney General, lied about being involved in the firings of federal prosecutors (from 19 April, 2007):

In recent weeks, Mr. Gonzales has carefully shifted his public remarks from at first denying that he was involved in any discussions related to the ousters to acknowledging that he had misspoke and that he might have participated in several conversations or meetings.

During the Abu Ghraib scandal, Donald Rumsfeld, then Secretary of Defense, lied about the abuse of prisoners in the custody of American troops (from 28 August, 2004):

But on Thursday, in an interview with a radio station in Phoenix, Mr. Rumsfeld, who was traveling outside Washington this week, said, “I have not seen anything thus far that says that the people abused were abused in the process of interrogating them or for interrogation purposes.” A transcript of the interview was posted on the Pentagon’s Web site on Friday. Mr. Rumsfeld repeated the assertion a few hours later at a news conference in Phoenix, adding that “all of the press, all of the television thus far that tried to link the abuse that took place to interrogation techniques in Iraq has not yet been demonstrated.” [...]On Friday, the chief Pentagon spokesman, Lawrence Di Rita, sought to play down Mr. Rumsfeld’s comments, saying: “He misspoke, pure and simple. But he corrected himself.”

In a particularly amusing use of the word, we have this statement from Alberto Fernandez, then a director in the State Department (from 23 October, 2006):

In the 35-minute interview, Mr. Fernandez, who speaks Arabic fluently, said, “History will decide what role the United States played.” According to a translation by CNN, he said that while the United States had tried its best, its role might be criticized by future historians “because undoubtedly there was arrogance and stupidity from the United States in Iraq.” Other news sources have translated the remarks in a similar way.[...]

In a statement released Sunday night by the State Department, Mr. Fernandez said:

“Upon reading the transcript of my appearance on Al Jazeera, I realized that I seriously misspoke by using the phrase ‘There has been arrogance and stupidity by the U.S. in Iraq.’ This represents neither my views, or those of the State Department. I apologize.”

Hm, “misspoke”, eh? Like he could have said something like that by accident? One can just see his bosses telling him to “take it back and say you’re sorry!”

Of course, the river has two banks, and there’s misspeaking on both sides of it. in 1995, Bill Clinton’s Secretary of State, Warren Christopher, told us that CIA financing of Guatemalan military intelligence had stopped, when it hadn’t. He then admitted that he’d lied (from 4 April, 1995):

The Clinton Administration conceded tonight that money was still flowing from the Central Intelligence Agency to Guatemala’s military intelligence services and said that the bulk of those payments would be suspended immediately. Senior officials said that Secretary of State Warren Christopher misspoke when he said on Sunday that the payments had ceased.[...]

On Sunday, Mr. Christopher, speaking on the CBS News program “Face the Nation,” declined three times to give a “yes or no” answer to questions about C.I.A. financing before finally asserting that he was confident that such payments had ceased.

“I’m satisfied there’s no money going down there now, that’s right,” Mr. Christopher said.

While one can, surely, pick the wrong word here and there — suppose Mrs Clinton had said that she’d dodged bullets in Bosnia in 1969, when she meant 1996 — or get a fact wrong by accident — if, say, she’d talked about arriving in Sarajevo, rather than Tuzla — that’s not what folks usually mean when they say they “misspoke”.

They usually mean they lied.

They mean that they tried to hide the truth, and they got caught.

Now, I don’t expect to hear public figures admitting that. But it’d be nice to see the media call them on it. New York Times columnist Paul Krugman used that waffle word in a column from October, 2004:

“As a result of the American military,“ President Bush declared last week, “the Taliban is no longer in existence.”It’s unclear whether Mr. Bush misspoke, or whether he really is that clueless.

Mr Krugman misspoke. He should have said straight out that either Mr Bush is entirely clueless, or he was lying. In an op-ed column leading up to the 2004 presidential election, that was what people needed to see, in black and white.

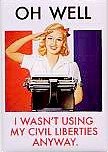

Let’s ban the word “misspoke” from the mainstream media. It’s too easy to shrink behind it and not address the fact that our leaders are lying to us. Call it what it is.

So, then, how about when the news media report that on Christmas day, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab “

So, then, how about when the news media report that on Christmas day, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab “