It’s that time of year: a Tuesday near the end of January. It’s just past another anniversary of the president’s inauguration, and time for the annual tradition, the State of the Union address.

In this case, it’s President Obama’s third anniversary, and tonight he’ll give his third SotU speech. According to the Washington Post, this year’s talk will stress a return to American values.

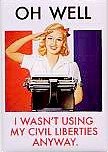

All right, here it is: I’m sick to death of hearing about values

. Values

has turned into a codeword for reactionary politics, repression, and censorship. I don’t want to hear a speech about those kinds of values

, especially from a president who has done little to fix the overstepping excesses of his predecessor, and, to the contrary, seems to embrace many of them.

American values used to be about freedom and opportunity, not control and rigidity. America was a country that didn’t abuse and arrest people for assembling peacefully. It didn’t arrest people for documenting how the police were handling situations. It didn’t keep political prisoners, detaining people indefinitely with no chance of formal accusation, trial, and defense. It didn’t limit the rights of people because of who they are, it didn’t restrict their access to medicines and medical procedures, it didn’t try to teach children mythology in science class, and it did not march a conservative Christian agenda down the streets everywhere.

You want to return to American values? Demilitarize the police, and get them back to engaging with the communities they serve and protect. Don’t send people off to secret prisons, close Guantánamo, and give everyone there a proper, open trial. Stop using terrorist

the way dictatorships have used denunciation, as a way to whisk troublesome people away. When people get angry and want to protest, encourage them and give them a venue, don’t beat them down and throw tear gas at them as they sit non-aggressively. Allow yourself to be held accountable for your actions, and don’t threaten people who want to record what you’re doing. Don’t get involved in people’s private lives and personal decisions. And keep religion out of the government and public education. You can start that by not saying God bless

in your speeches. Try it tonight.

Remember that American values came from our flight from having to live under someone else’s values. We can’t just replace the king’s values with those of your family, your church, or any other relatively small subset of Americans. Our values were set up to protect our rights and our freedom — everyone’s — and that is what we need to return to.

Oh, and fix the economy, yeah? Don’t just talk about it.