There’s a guy in Arizona — yeah, Arizona, that noted hotbed of anti-liberalism that fosters (I want to say festers

) delightful folk like Joe Arpaio, Ev Mecham, and Russell Pearce (not to mention John McCain) — who’s having a fight with his homeowners’ association about the flag he’s chosen to fly. The association allows a handful of flags that are specifically listed in Arizona state law (in other words, they can’t stop you from flying those), but Andy McDonel is displaying a different one, the Gadsden Don’t Tread On Me

flag.

They don’t like that.

Now, Mr McDonel says that his use of the flag has no connection to the Tea Party movement, which has recently adopted it. It’s a patriotic gesture,

he says. It’s a historic military flag. It represents the founding fathers. It shows this nation was born out of an idea.

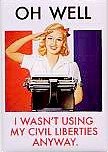

I don’t really care why he wants to fly it. I only care that no one has any moral right to tell him that he can’t. And, as yesterday, this is my opinion, not coming from any legal expertise (and this time legal precedent is against me). Similarly, folks who are proud of their heritage have every right to display a Union Jack or an Irish flag, a French or German or Italian one, an Israeli flag, a Palestinian flag, an Egyptian flag, or an Iranian flag, if that’s what they want to do.

The problem is that homeowners’ associations, as they currently exist in many places, should simply not be. They have turned into organizations of fascist bullies, they have no place in a country such as ours, and they should be outlawed.

Their premise looks appealing, at least to many people: folks in a community want to get together and make sure their community meets a reasonable set of standards. They want a neat community, a pretty community, a community that maintains high property values. They want to make sure people keep their lawns trimmed, don’t let their houses fall into disrepair, don’t paint their houses unattractive colours, and don’t have half-disassembled cars parked in their driveways in front of God and everybody.

The problem is that what’s an attractive colour to me might not be to your taste, there’s a difference between a two-day rebuilding of a classic Mercedes engine and half a dozen broken-down jalopies that have been sitting around for two years, and some people prefer other sorts of ground cover to grass lawns. Homeowners’ associations do not take such reasonable variations into account.

They are, in general, authoritarian and lacking in any flexibility, taking people to court for minor violations, forbidding people from making normal use of the houses and land they bought, and seizing people’s property, sometimes for just being a month or two behind on their payment of association fees.

Places without associations deal with the same issues of community standards, but it’s done by peer pressure. There are ordinances, to be sure, that address health and safety concerns, so one mayn’t throw one’s garbage on the front lawn and leave it there, and one must repair exposed electrical wires, broken glass, and the like. Beyond that, well, if one is in the habit of mowing only every two months, one will hear suggestions — sometimes gentle, sometimes less so — from the people next door and down the street. It works well enough.

Not well enough for some.

Well, hey, you say, you know the rules when you move in. Just don’t buy in such a community. As the lawyer for the Arizona HOA in the Times article says, Bottom-line, anyone considering residing in a community association should carefully review the association’s governing documents beforehand to ensure that the community is a good fit for them.

The problem is that people often have little choice in the matter. In some areas, HOAs are ubiquitous, as all new communities have had them for several decades. Where I live, I can make that choice. In other areas, that’s not true.

What’s more, people often find themselves violating things they never imagined would be a problem when they moved in. Rules change after you’re there, and unless you were right on top of it and had the time to garner a large base of support to defeat the proposal, you’re stuck with the result. In new communities, the developer often retains a controlling vote on the association board anyway, so it doesn’t matter how much support you can get.

Years ago, a friend of mine found the outside of her back fence vandalized with spray-painted graffiti... and then was told that she had only a week to paint over it, or face fines. Ah, and the paint had to be exactly colour X, purchased from the local store. Another friend with a white house and green trim found that he liked the blue trim of another house down the street. He was told that the colours were planned from house to house, and even though he wanted to use an already approved colour, that colour wasn’t assigned to his house. He would have to apply to the association board — and, here’s a surprise, pay a substantial, non-refundable application fee — and hope that they said yes to the change.

And then there are the foreclosures.

Of course, we do limit the HOAs in some ways. Much as some might want to, they may not refuse to allow blacks, Hispanics, or gays into the neighbourhood, for example. Yet, they can make everyone live their lives in the same white-bread middle-of-the-road way, under threat of losing their houses. This isn’t right.

They’re just abusive, tyrannical bullies, bent on telling everyone else what to do. They have to go.